Oct. 1, 2022 – Courtenay roamed more Seoul neighborhoods and palaces today while I went to the Korean Demilitarized Zone, the tense, jagged line separating South and North Korea. Courtenay would have come along but she was rightly concerned about COVID and spending the day in close quarters with a group, a worry that was born out when my seat mate in a small van introduced himself and said he’d just come out of quarantine after testing positive upon arrival to Korea. We didn’t shake hands.

The truth is there is not that much to see at the DMZ, but there is a lot to think about.

It is one of the world’s saddest, strangest tourist attractions, the only place I’ve ever visited where they sell pieces of barbed wire in the gift shop. Former President Bill Clinton called the DMZ “the most dangerous place on Earth,” and perhaps, outside of Ukraine, it still is, with major armies stationed only a few kilometers apart, signs lining the roadsides warning about unexploded mines, and North Korea sending menacing messages by firing long-range missiles almost every day this week.

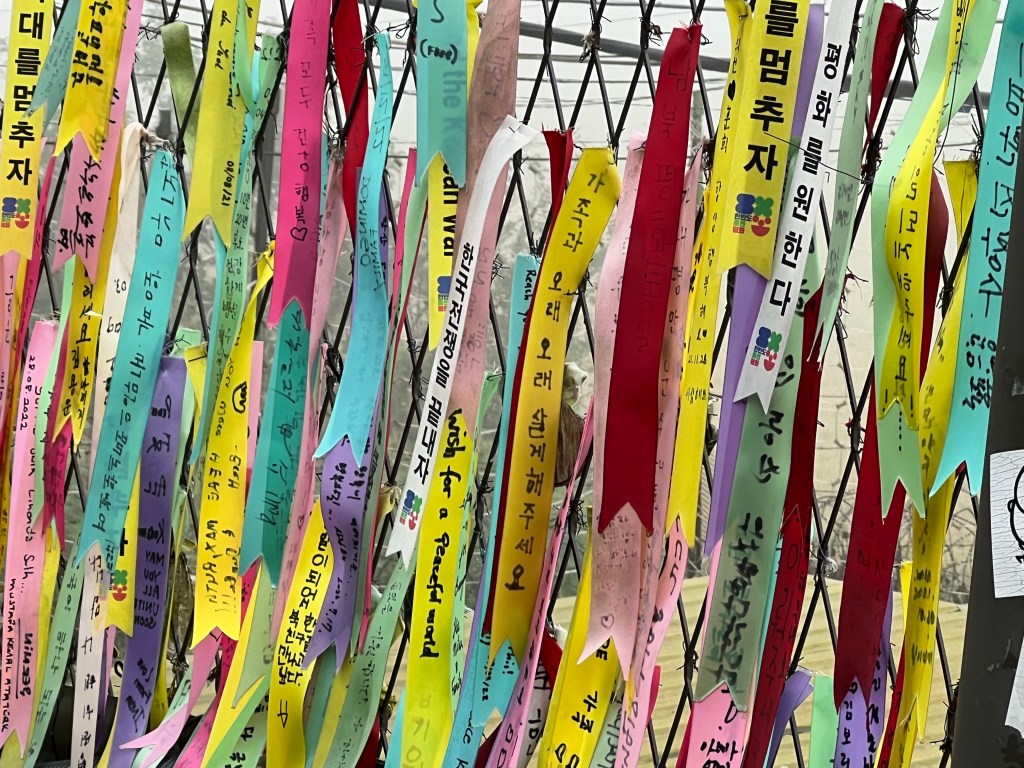

But on this warm autumn day, the fields of rice in the farms around the Korean military checkpoints ripening to a yellow-gold, the DMZ was quiet, almost serene. Fluttering in the light breeze at our first stop, Imjingak Park, the last village on the South Korea side, were thousands of ribbons attached to a fence. Our Korean guide, Nancy Kim, explained that the ribbons carried messages—news of births and deaths, messages of love and lost and longing, from South Koreans to their long-lost relatives in the North. No contact—no phone calls, no letters, nothing—is allowed between North and South, where millions of families were separated when the war ended. The South Koreans place the ribbons in Imjingak hoping that the wind will carry their messages of love into the North. There is also a concrete platform, the Mangbaedan altar, where families come to leave offerings, pray for their lost loved ones, and, Nancy said, cry and cry and cry.

So, no, this isn’t your ordinary tourist destination. We saw the remains of the Freedom Bridge, a now abandoned wooden bridge where more than 10,000 prisoners were exchanged at the end of the Korean War. We then walked down deep into one of the “infiltration” tunnels that North Korea dug beneath the DMZ, apparently as a prelude for an invasion. The South has discovered four of these tunnels; it’s believed there are another dozen or more undiscovered. It’s a long, cramped thirty-minute round trip down deep below the DMZ, where the tunnel is now blocked with three concrete walls, just a few feet south of the military line of demarcation. We went to an observatory on a high bluff overlooking the DMZ, where we looked across the line and see North Korea. It was mostly forested, not farmed like the South side, and through the binoculars atop the observatory, you could see the buildings of Kaesong, the closest North Korea city. From that distance, it looked just like any other small city shimmering in the mid-day light.

It was a mind-bending day. I came back in the mid-afternoon, met up with Courtenay, and later we went out into the Saturday night maelstrom of Seoul, which was, in such a dramatic contrast, incredibly vibrant and alive, with thousands and thousands of people on the streets, dancing to K-pop music, shopping, eating, a huge group marching around City Hall loudly protesting something.

Meanwhile, the quiet stillness of the DMZ was less than an hour away.

So much to think about. Thank you.

Hello Angie. Hope things are still going well with Pippy and that you found a more comfortable sleeping arrangement.

Great, Quality Content for The Ultimate Tour Guide, A lot of thanks for sharing, kindly keep with continue !!