Author Archives: Rick Attig

Cordoba aglow: A beautiful city, a call to prayer

March 13, 2025 — Cordoba, Spain — A light rain and a hair-raisingly sharp turn into the car rental return parking garage greeted us on our arrival in Cordoba, after a pleasant drive from Ronda with a memorable stop at the megalithic stone dolmens at Antequara. We had a wonderful lunch, by a huge hearth with an actual fire, at a roadside restaurant, the Caseria de San Benito, and drove the wide-open highway on into Cordoba. The only challenge of our van rental was on arrival in Cordoba, when all three passengers had to get out of the car and help Rick make it into the garage, with three-quarters of an inch on each side of the van to spare. In a gentle rain (yes, it has rained the entire time we have been here), we got our first look at a city that has a remarkably rich history stretching several thousand years with Carthaginian, Roman, Visigoth, Muslim, and Christian eras.

Our experiences in Cordoba began on the rooftop terrace of an historic hotel, formerly a 17th-century convent built around three courtyards, where we shared a bottle of champagne while rain tapped on the plastic shelter above us. One by one the city’s lights came on, illuminating the incredible Mezquita and its bell tower, only a hundred yards or so from our hotel. Like so many religious sites Spain, it has a long history – Roman temple, Visigothic church, Islamic Mosque, Christian cathedral. Though most of the Catholic rulers built their huge cathedrals to completely cover the large mosques, Cordoba is unique in that they left much of the mosque intact, but instead set a large cathedral in the center of the former mosque. As we looked over the Mezquita, in the distance we could hear a Muslim call to prayer. It was a moment that perfectly captured Cordoba, where Muslim and Christian history, rituals, and tradition–and even architecture–are intertwined in deep and unique ways.

Cordoba began as a Roman settlement, and we caught glimpses of its early Roman roots, including pillars and stones repurposed into the corners and walls of more recent buildings–some well over two thousand years old. Six pillars from a Roman temple still stand not far from Cordoba’s main square, the Plaza de Corredero, a formerly used as a bull-fighting ring. But it was the Muslims who built Cordoba into one of the world’s great cities, from the eighth to the 13th centuries. It was the ancient, or the ancient Alexandria, a center for intellectual, poets, mathematicians, and thinkers, Islamic and Jewish. A famed Muslim leader, Abdel Rahman I, a refugee from the Abassid coup over the Umayyads in Damascus, Syria, arrived in 756 and made himself emir, and he launched the golden ages of Cordoba. The city became the Ancient Rome of the medieval world, a great center of Muslim culture and learning, with over 300 mosques and 80 libraries.

For us, Cordoba was aglow with light and shiny with rain as we left the hotel and walked to the Puente Romano, the one-time Roman bridge that spans the Guadalquivir River, which flows downstream through Seville to the ocean. With all of the rain, the gushing river was running high and muddy. The bridge was originally built after Caesar’s victory over Pompey the Great. Later a Moorish bridge was built on the foundations of the Roman bridge. That’s the span that we walked across, sheltered by umbrellas, looking back at the soft yellow stones of the illuminated Torre de la Calahorra, a 12th-century gate tower that once functioned as part of the city’s medieval fortifications, and was the site of fierce fighting when the Catholic King, Fernando III, brought his troops to Cordoba during the Christian Reconquest in the 13th century. Now it’s a museum that celebrates the period in history when Christian, Jewish and Muslim communities of Cordoba lived in harmony. We felt that special blend of history, walking the atmospheric maze of streets in the Juderia, the Jewish Quarter, including the colorful Calleja de las Flores, lined with hanging flower baskets, and emerging with a spectacular view of the Mezquita Mosque-Catedral, a UNESCO Heritage Site, and one of the most incredible places we have ever visited.

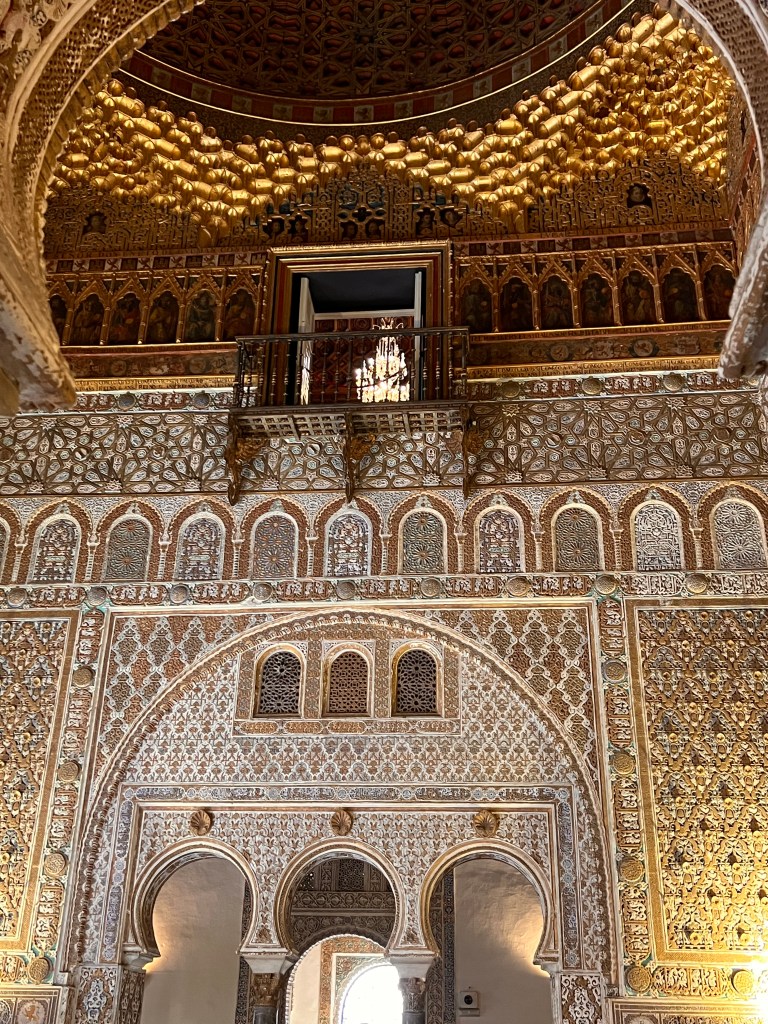

The Mezquita’s immense size and beauty is hard to describe, or even photograph. It was founded as a mosque in 785, built over the top of a Visigothic Church. It was an enormous mosque, large enough to fit more than 20,000 faithful. The praying space is a sweeping area of hundreds of honey-colored pillars (repurposed ancient Roman columns) with stripes of red brick. For three centuries, this building was the focal point of Muslim life in the city and inspired countless artists and intellectuals. The poet Muhammad Iqbal, for example, described it has having “countless pillars like rows of palm trees in the oases of Syria,” while the people of al-Andalus said that its beauty was “so dazzling that it defied description.”

We’re all so fortunate that this building survives. Charles V, the Holy Roman Emperor, instructed the Christians to not destroy the Cordoba mosque, now the only surviving one in Spain. He recognized its magnificence. However, the Christians did a major remodel, and in the 16th century build a massive baroque church in the middle of the mosque. It’s a mind-bending, unforgettable place to visit, wandering first through all those Muslim pillars and all that praying space, only then to emerge into a soaring cathedral space chock full of Christian imagery.

We saw a lot of other things in Cordoba, including a fun glimpse into the famous gardens and patio courtyards of Barrio de San Basilio, another part of the city’s Unesco World Heritage. The bronze medal winner of last year’s patio competition, the owner proudly showed us her courtyard, the walls filed with flower pots and ancient Roman mosaics scavenged from somewhere, while her son-in-law prepared lunch in a nearby kitchen.

But it was the breathtaking Mezquita, where we climbed the bell tower built atop the minaret of the former mosque, and where we could see century after century, wave after wave, of the people and religions that settled, built, and ruled, this part of the world.

Pact of silence: Walking past the bullet holes

MADRID, Spain — March 6, 2025 — All the guidebooks say the same thing: When you come to Spain: don’t bring up, don’t ask questions, say nothing about the Spanish Civil War. Almost 90 years after the war, which was triggered by a Nationalist military coup against the democratically elected Republican government, it’s still too sensitive, too raw. And, supposedly, Spaniards of all sides “agree” on what they call a pact of silence about a terrible war that saw hundreds of thousands of military deaths and executions, and culminated in four decades of Fascist rule.

So, on this, our first morning in Madrid, we had many questions about the Spanish Civil War, which we knew mostly through Hemingway’s wonderful novel “For Whom the Bell Tolls.” We took a remarkable tour with Almudena Cros, an historian and guide who leads walking tours that are a tribute to the Spanish Republic, the International Brigades, and the forgotten victims of Fascism. We met at the Ciudad Universitaria, the City University, and as a light rain fell Almu led us onto the campus where students streamed in and out of buildings pockmarked by bullets and masonry damaged by mortar rounds. The university is where Republican forces stopped the Nationalist march on the Spanish capital, Madrid, and where, from a maze of trenches, both sides battled for years.

It’s hard to imagine a more powerful example of Spain’s pact of silence, its collective refusal to talk about, acknowledge, or even remember, what occurred after its Civil War broke out in 1936, than to learn that every day thousands of college students walk in and out of buildings riddled with bullet and mortar holes and other damage from the war, and yet are generally oblivious about what happened there less than a century ago.

Almu walked us briefly through the history of the war in Madrid, showing us historic pictures of important sites during the war. We went into a nine-story building that was built on the site of the Hotel Florida, where Ernest Hemingway and many other international journalists had stayed and worked during the war. We saw the Plaza Mayor, where Nazi bombs had carved huge holes. We walked down some of Madrid’s most beautiful, and most lively, streets and compared them with Almu’s black and white photographs showing these same streets lined by crumbling buildings and rubble. How many of the thousands of people on those streets today know what happened there?

Almu fiercely believes it’s past time for Spaniards, and their government, to have more honest conversations about the war, to put up plaques and memorials that tell more fully, more truthfully, what happened. She seems to be a fairly lonely voice. Spaniards, it seems, are against digging into this part of their history, even refusing, in many cases, to unearth the mass graves of those executed during and after the war.

Thanks to Almu, we had an unforgettable introduction to Madrid and to the history of the Spanish Civil War. Her advice to visitors to Madrid, and her wish for those students that we walked past today, is this: Ask questions, notice the bullet holes, remember what happened there, and why, and take time to honor those who lost their lives fighting to defend democracy in Spain.